Celebrating French/American Relations Through These and Other Objects in the U.S. Ambassador’s residence in the Hôtel Rothschild

Collaborative blog by Elizabeth Wise, Kaitlyn Munro, Katherine Hill McIntyre, Julia Brennan

All images are courtesy of Caring for Textiles unless otherwise noted.

The Lights that Guide Us: A Celebration of Hôtel Rothschild et son

Jardin Pontalba & the Franco-American Legacy

An exhibition celebrating 50 years of U.S. Ambassadors’ residence in the Hôtel Rothschild, as the house is known today.

The exhibit is open June 10, 2022–October 1, 2022

On a site chosen originally by the Chancellor to King Louis XIV, the 1842 residence was built by the Baroness de Pontalba of New Orleans. Minutes from the Louvre and just yards from the presidential Elysée Palace, the house’s gorgeous gardens are a park in the center of Paris.

After the Baroness’s death, it was bought by Baron Edmond de Rothschild of the banking family. The family was forced to flee to Switzerland during World War II, and the US Government purchased the building in 1948, becoming the residence of the American Ambassador in 1972. With considerable help from the Rothschild family, the residence has regained the splendor of that era.

The show celebrates that era and French American relations through a mixture of historical and contemporary objects, including the clothing of diplomacy. Among the items on display are the World War II uniform of a Monuments Man, representing the Allied effort to recover works of art looted by Nazi Germany. The exhibit also highlights the rich exchanges in popular culture, featuring art by the painter Ellsworth Kelly and, of course, the American-born singer and dancer Josephine Baker, who adopted France as her homeland and was just last year (2021) interred in the Panthéon, France’s temple to its great heroes.

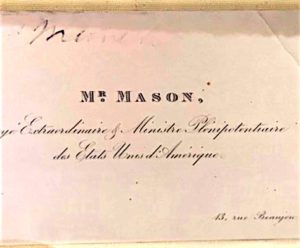

Mr. Mason’s suit holds pride of place on display in the Ball Room. The Minister Plenipotentiary would no doubt be pleased to see evidence of the continued friendship and cultural exchanges between his home and host countries.

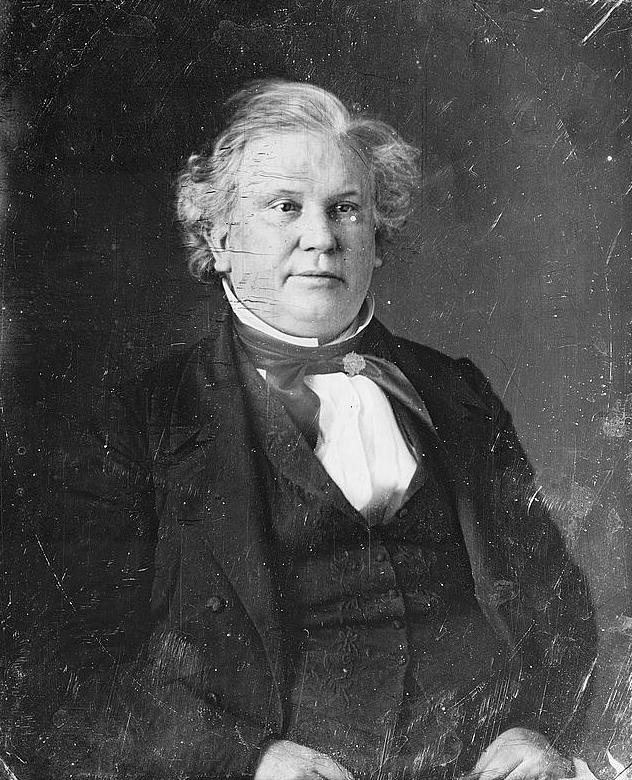

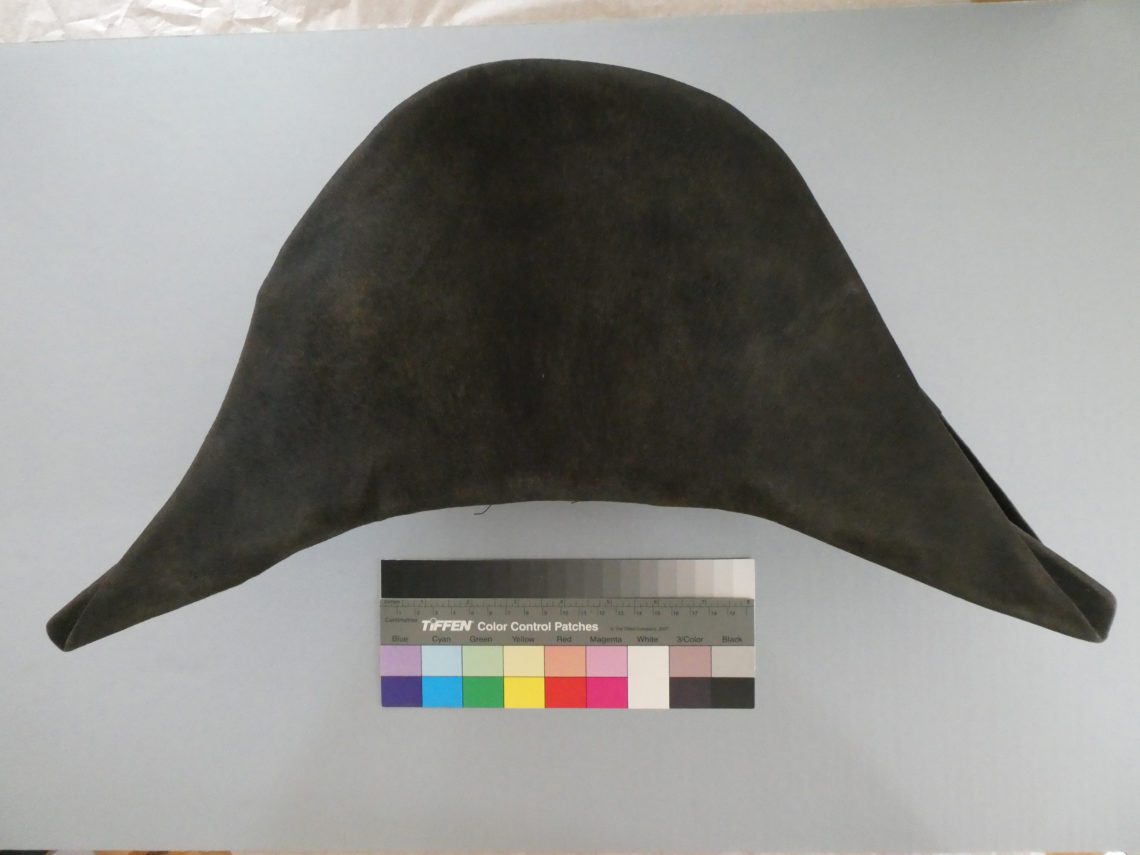

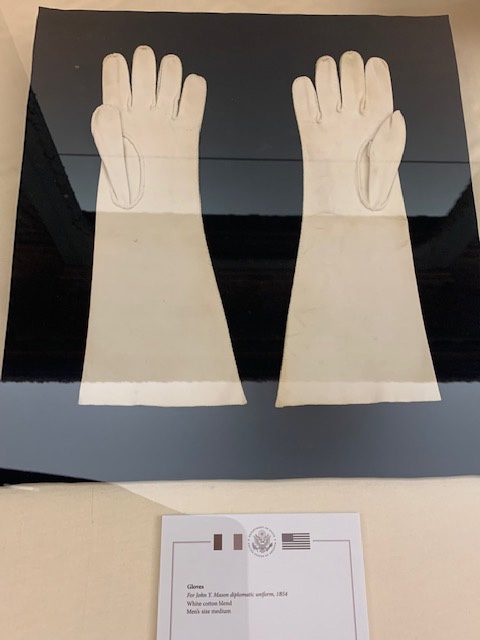

Our subject John Y. Mason (1799–1859), was probably a larger-than-life personality. This Virginia-born man served as Representative from Virginia, Secretary of the Navy, and Attorney General of the US before serving as the US Minister (called Ambassador today) to France. Posted in Paris from 1854–1859, during the period of Napoleon III, he wanted to look as debonair as the other international diplomats, so Mason had this stylish uniform made in Paris. Candice Nancel, Cultural Heritage Manager at the US Embassy in Paris, tells an amusing story about the suit: “The US government, aka US Secretary of State William L. Marcy, thought it was too ostentatious, and reprimanded Mason for it. They thought that he should be wearing what an American would wear, and he wanted to wear what was worn here. He was reprimanded for dressing up too much!”

He was reprimanded for dressing up too much!

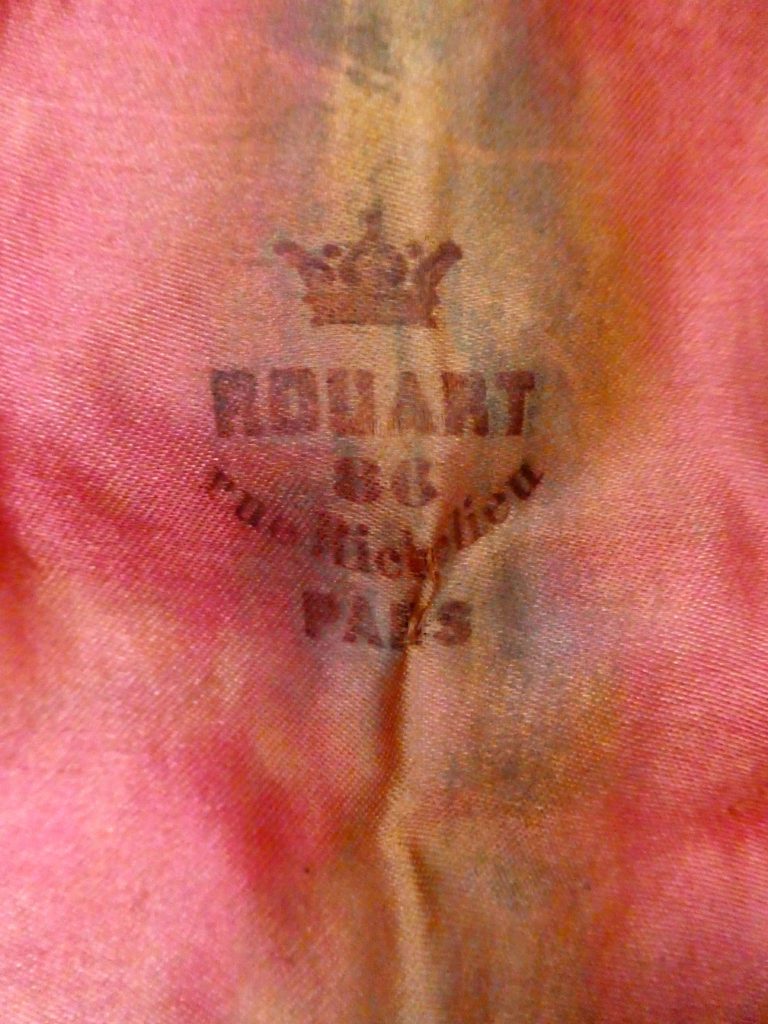

To celebrate Mr. Mason’s ‘individualism’ and style, the ensemble was conserved before being shipped to Paris for display on a custom-made mannequin. While each uniform piece required gentle surface cleaning and some sprucing up, the tailcoat was the focus of more extensive treatment.

Using a typical textile conservation technique to stabilize shattering linings and slips, sheer fabric overlays (like silk organza) were secured over the whole lining using fine hand stitching. This overlay protects the damaged lining from further abrasion and loss. And the translucence of the fabric allows the original lining material to be seen.

For display, the jacket needed to be fully buttoned. Horizontal cuts aligning with each button slit were made through the new silk repair lining. Raw edges were then bound with tiny pieces of adhesive-treated sheer silk. The edges of the bound buttonholes (Jacket and new organza overlay) were delicately stitched together. An elegant, long-lasting functional solution and one that any tailor will admire.

A 19th-century uniform requires a carefully made custom mannequin. The goal was to show the suit in the most dapper way possible while carefully supporting delicate parts and disguising a rather large waistline.

Let’s take a peek at what’s underneath:

Using various archival padding and building materials – ethafoam, high loft polyester batting with no resin, polyester felt, cotton stockinette (used for covering casts), and cotton jersey – the body form was shaped and styled to support the jacket and trousers. Removal of arms and legs makes the mannequin easy to assemble and take apart for its journey back to the United States.

https://oboculturalheritage.state.gov/exhibitions/the-lights-that-guide-us/

Thank you to Candice Nancel, Cultural Heritage Manager at the Embassy of the United States in Paris, Curator Joseph Angemi, and the staff of U.S. Department of State Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations.

All images are courtesy of Caring for Textiles unless otherwise noted.

Again, more excellent work from Caring for Textiles.

Quite right Mr. Mason, when in France you can never dress up enough!

Thank you for giving a glimpse into what is involved in restoring clothes that are almost 200 years old and displaying them. Now I’m more aware when I see other similar exhibits.

I admire the detail in the conservation work and I the wonderful storytelling! To add about Josephine Baker, a new promenade built out on the pier over the port of Cannes has been named after her!

Want to see it! Am headed for Paris!