By Peyton Bramble

In the field of history, there is a subsection that is less known: Public History. As a recent graduate from Shippensburg University with a BA in Public History, I was able to experience Public History first-hand through the lens of open conservation.

The concept of open conservation is to “pull back the curtain” on all the detailed actions that go into preserving artifacts and preparing them for exhibition. Traditionally, the work of conservators was exclusively secreted in labs and private ateliers. Conservators were put in windowless labs (to prevent light damage, of course; we are not monsters) where a multitude of scientific and hand skills are employed to analyze, clean, repair, and prep objects, extending their lives for the generations to come.

The goal of open conservation labs is to “connect with art, science, world cultures, and history in ways that engage and delight,” as explained by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts which opened its public access conservation lab in 2020. This initiative is one with roots in 2000 that began with the opening of the Lunder Conservation Center at Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC after a six-year construction process with its official opening in 2006.

As a public historian,

I think open conservation is great.

– CFT Intern Peyton Bramble

As a public historian, I think this initiative is great! It takes ideas that interpretive museums have been trying to achieve and does it on a large scale. By creating a looking glass into the lives of conservators, it shines a beautiful light on what it means to be in the museum studies field, handling and caring for the objects that the public enjoys. That being said, in practice open conservation manifests in different ways, some more successful than others.

At the University of Penn Museum in Philadelphia, there is an artifact lab that provides visitors with in-person tours of what is being worked on. Guided instruction and thorough explanation are available. This is good interpretive history. By having a knowledgeable person from the field right there to take questions from curious children or inquisitive adults, the experience is enhanced for all. It is a conversation; it helps bring to life the human stories centered around the repair of these artifacts and the profession. The conservator has a direct way to share their own messages around the importance of conservation, and the visitor gets the scoop as to what goes on behind closed doors, and hopefully learns something too.

Another good example of an open conservation lab is The Conservation Center in Chicago, IL. As the largest laboratory in the country, it has certainly earned its name as The Conservation Center. The Conservation Center schedules private tours in which the CEO Heather Becker takes guests behind the scenes. “Guests are encouraged to engage with conservators and learn about the latest conservation techniques in each discipline. Conservators will introduce a current project and share insights on preservation and care of artwork.” While not a museum, The Conservation Center in Chicago handles the topic of open conservation effectively, providing both guests and conservators with an engaged and unique experience. Coming back from the pandemic, the Conservation Center has slowly started resuming its private tours on a case-by-case basis but prior to the pandemic, they averaged about two tours per month.

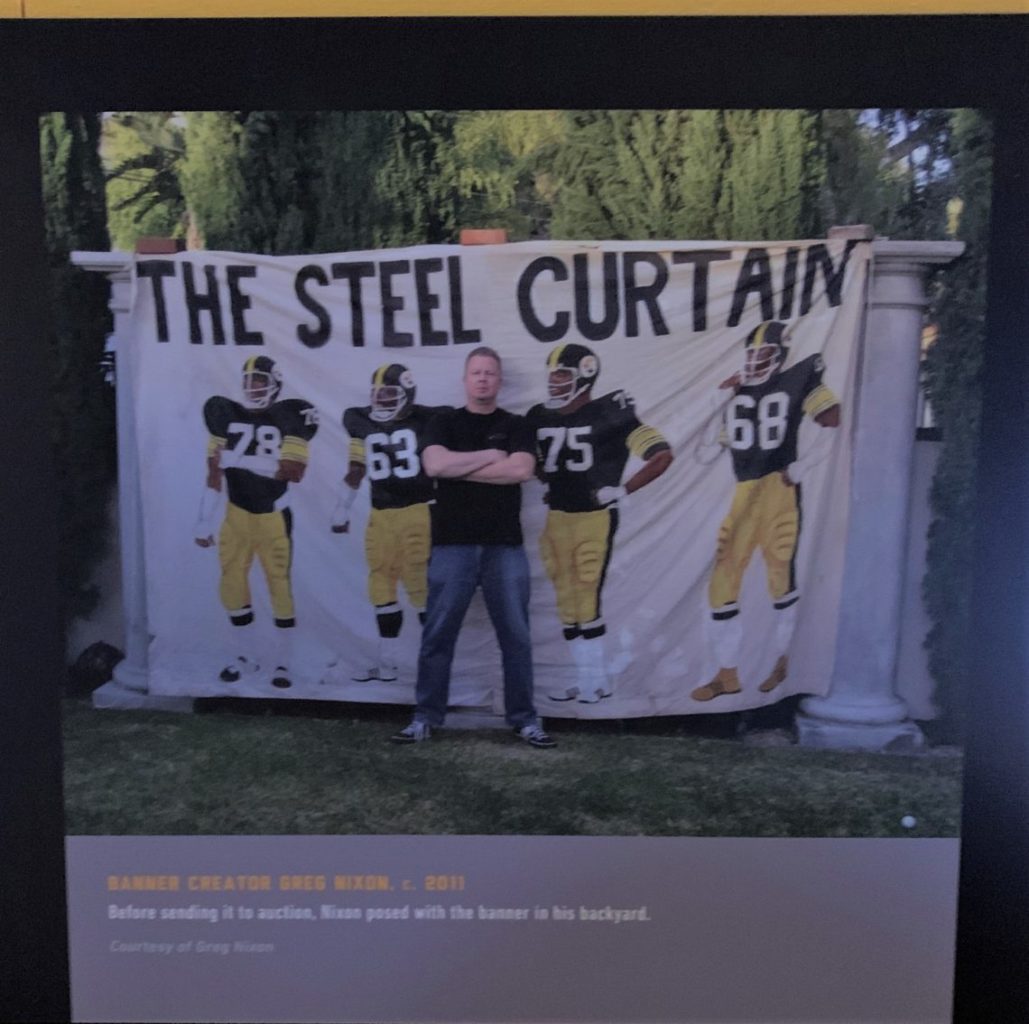

In June I joined the Caring for Textiles team to work onsite at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, PA. Our focus was a really large textile – a 1970 banner celebrating the Pittsburgh Steelers. It was hand-painted by a fan and depicted the four defensive linemen that made up the ‘Steel Curtain’. To have a space large enough to treat this banner, we set up shop in the Grace M. Compton Conservation Lab. One long wall of glass windows faced a huge exhibition space. This perspective was like being in a fishbowl; we had suddenly become our own exhibit.

Our first day was a bit of an adjustment—glancing up from hand stitching to see camera flashes and an audience. Eventually, the outside world just faded away and we were alone and absorbed in our work. But I noticed a recurring pattern over several days: people would simply stand at the glass for a minute or so, observe, and then move on. It seemed a bit like reading a label. While our work was easier not being interrupted to answer questions, I was a little bothered by it, this passive encounter. Granted, the Heinz History Center does not have a permanent conservation team, but the lab is used for many object-based purposes, and it seems that signage, or scheduled open question sessions would make the reality of open conservation a lot more dynamic and informative, and to serve its purpose.

This particular example of open conservation had no two-way understanding or communication. From a distance, the repairs and treatment we were doing on the banner were nearly impossible to see, much less comprehend. The most audiences would glean was that we were probably fixing the banner in some way. With conservation being fairly invisible over the last century, the average museumgoer has no real idea of what the work or profession entails. With no one to explain it, no signage, walkie-talkie with conservators, or active film clips…it will remain that way.

A majority of the general public does not realize this profession exists; I did not even know about

open conservation until I did an internship in a museum.

Open conservation is an exciting initiative for both worlds of conservators and public history. Shining a spotlight on the details of preservation work provides a window into how important conservation is to the long-term success of museums and their collections. A majority of the general public does not realize this profession exists; I did not even know until I did an internship in a museum. What a discovery for me. Our field is significant and integral to preserving cultural heritage for all, and allowing public access is really important.

In conclusion, the design and management of open conservation needs to be thoughtful in order to be successful. Having signage or someone knowledgeable onsite is necessary for the success of an open conservation program. Giving visitors that access and conversation is a necessary component. A glass window is not enough. If done well, open conservation labs or planned public art restoration projects are a large step forward in supporting successful public history.

Sources:

http://www.theconservationcenter.com

https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/museum-conservation-center/preservation

https://www.mfa.org/collections/conservation-and-collections-management/conservation-center

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-jul-02-ca-smithsonian2-story.html

https://americanart.si.edu/art/conservation

Spot illustrations from Adobe Stock.

Great piece. Nice work Peyton.

I agree 100% that we need to be more open to visitors, who find our work extremely interesting.

For myself, I am happy to be part of the Summer Teachers’ Institute at the Bennington Museum, in Bennington VT, each summer.

I look forward to this each year, because it gives me the chance to teach the teachers, about the conservation profession.

It’s not a chance for them to see live conservation happening, but by doing a power Point presentation, it opens their eyes to our field.

The teachers then pass on this info to local K-12 students.

This can only be good for our profession.